I’m a 24-year-old law student and public health activist based in Boston. I’m an alumna of AmeriCorps Community HealthCorps and founder/co-president of my school’s chapter of Students for Sensible Drug Policy. I’ve worked in community health centers, legal services agencies, and public defenders’ offices, and I am deeply invested in ending the Drug War and the War on Poverty.

Though I’m a Spanish speaker who’s lived and worked in NYC, I’ve unfortunately never had the chance to visit the countries I’ve heard so many of my clients recall. This page is here to help me collect enough money to be a delegate to Colombia with Witness for Peace in January. The costs and accommodations of the 10-day trip are modest, but beyond my capacity as a student. I am hoping to reach folks who care about the same issues as me and want to participate, a little, in my professional and personal development as an advocate.

The War on Drugs has resulted in countless casualties and unquantifiable suffering throughout the Western hemisphere. From the lives destroyed by prescription drug abuse in the U.S., to the horrific violence along our border with Mexico, to the livelihoods “eradicated” by militarized police in Colombia—we are all suffering from the crusade of prohibition.

For nine days, the cost is $1450, everything included (food, lodging, transportation, etc.). I’ll also need to purchase a plane ticket, likely to run another $800. I’m asking for help from friends and family in raising $2300 to finance this trip and make this dream a reality!

Please give only if you are able and inclined to do so. Thank you for reading. Now back to your scheduled programming.

This was my earnest plea to friends and friends-of-friends back in August, when I started a campaign to raise enough money to travel on a Witness for Peace delegation examining the failed War on Drugs policies in Colombia. By the end of September, I had a few hundred dollars, but raising the whole amount wasn’t looking very realistic.

Then came my first real fundraising success, at the Students for Sensible Drug Policy Northeast Regional Conference in Providence, Rhode Island.

My table @ the 2012 Northeast Regional SSDP Conference in Providence. (Photo credit: Devon Tackels)

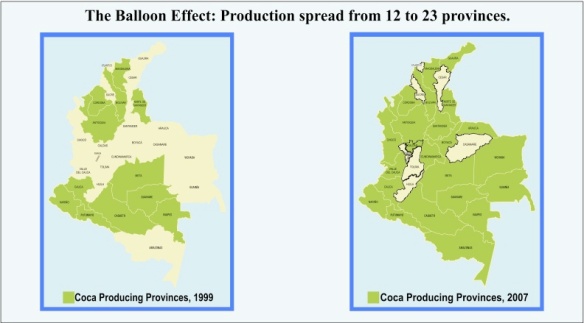

Lizzy and Devon, the amazing organizers, helped me set up a table next to their check-in, and I got to chat with SSDPers about the effects of coca eradication and the global War on Drugs in Latin America. I’d set up my MacBook to play Shoveling Water, a documentary produced by Witness for Peace in 2009. Unbeknownst to me, Sanho Tree (who is featured in the film) was a scheduled panelist at the conference. It was a bit surreal—but awesome!—to meet him (director of the Drug Policy Project of the Institute for Policy Studies) and talk to him in person, while a digital version of him, on the screen next to us, compared clandestine coca paste production in the Andean jungle to rural Appalachian moonshine operations under alcohol Prohibition during the 1920’s. Other SSDP alumni and current chapter leaders helped put me over the $500 mark that weekend.

During October and November, my fundraising efforts were put on the back burner due to a rigorous grad school courseload. Still, I made the effort to incorporate learning about coca eradication by putting together a presentation for my Public Health Biology course on the biochemical mechanisms of glyphosate—the active ingredient in the commonly used Monsanto herbicide, Roundup®, and its generic formulations. Along the way, I learned quite a bit about industry toxicity hazard assessments and their faulty assumptions (and I’m saving that for another post).

On November 4, I’d raised enough money from classmates, former co-workers, supervisors, teachers, family, and even strangers to cover the entire cost of my round-trip plane ticket (final cost: $910.49), and then some. When I booked that ticket, I committed to become part of the delegation, one way or another—no excuses and no turning back!

So I started to talk more, to everyone I know, about why this is no vacation—why it is a personal and professional investment in my future as an advocate. I talked about the year I spent as an undergraduate reading and writing about youth involved in narcotics trafficking and armed conflict in Medellín and surrounding areas. I talked about the damages of drug prohibition in the form of violence, mass incarceration, displacement, and addiction. I talked about my dear friend Liliana, who grew up in Barranquilla and got me hooked on afro-Colombian funk through her excellent musical collective, M.A.K.U. I talked about the time I spent in the Bronx as a community health worker, environmental and social determinants of health, and the collateral consequences of incarceration and addiction. I got to meet Jessye (permanent staff member with Witness in Colombia) when she accompanied Ligna Pulido to Boston to give a talk at NUSL on indigenous women’s movements in Colombia—another example of the serendipity of this opportunity’s timing. I applied for and was granted conference funding through the Tufts PHPD Student Activity Fund. And finally, by the start of December, I’d raised over $2200 in total and it finally started to seem real.

The icing on the cake was that my birthday this year coincided with a very dear Northeastern Law tradition, the annual NLG party upper-levels throw for the 1Ls to celebrate being done with their first law school exams. After an adorable birthday potluck and gift exchange with my wonderful JD/MPH cohort, I headed over to the party, where the organizers had graciously assembled all of my favorite Fall/Spring friends to help me celebrate! It was amazing to stand in a room full of inspiring, bright people who all supported me (financially or otherwise) on this endeavor.

Over the past few months, I have been touched and humbled by the outpouring of support from folks I have known in many different stages of my life. Many of you got back in touch after years apart, to support my upcoming journey to Colombia. I honestly never imagined that I would actually raise the money to afford this trip, but you all came through and here I am.

Thanks to every single person who supports me and encourages me and inspires me to dream big. I leave January 4 and return on January 16. Much more to come.